|

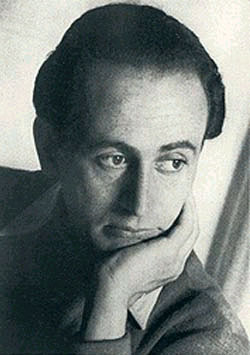

| Nathalie Lemel |

The disastrous (and utterly unnecessary) war with Prussia and the huge French casualties; the winter-long siege and bombardment of their city, along with the paralysis of production, employment and income and the shortage of food; the sense of national humiliation before Prussia and of betrayal first by their Emperor and then by a new government that promised only greater exploitation and the elimination of hard-earned rights; and the anxiety produced by all this and so little expectation of relief — these were all components for combustion of a large, proud, densely populated city, suddenly abandoned by its government and police forces. Without knowing any more, we might expect riots, crime, vandalism. Instead, we see a social revolution where hitherto unknown men and women rose to police the city, maintain the roads, hospitals and schools and keep the factories and commerce functioning, all the while fighting to defend it and making all major decisions even as to military defense by majority vote, for a few weeks from March 18 to the end of May, «au temps des cérises», spring 1871.

Why, I wonder, were bookbinders so prominent? Not only the energetic and audacious Eugène Varlin and the woman he encouraged in the leadership in the bookbinders' union he created, the equally amazing Nathalie Lemel. There were many others, now anonymous, among the most active communards. Was there something about the way they used their hands and all their senses in their craft that made them especially quick to react and adapt to rapidly changing circumstances? Or was it mainly their contact with books that enabled them to envision a better world?

And the other crafts. What about all those metalworkers who died at the barricades? And seamstresses? Hands and hand skills, hearts, neighborhoods, trade affiliations — everything is relevant when your fighting with all you have and for all your worth. Every known detail I discover helps me imagine the others.